Show Categories ››

Category: Crachesi in America

October/Ottobre 2022 Newsletter~English

September 27, 2022

in category: English Versions, Newsletter Archives, Craco Society News, Craco Vecchio, Crachesi in America, Religious Life, Craco Today

Comments Off on October/Ottobre 2022 Newsletter~English

April/Aprile 2022 Newsletter – Italian

March 31, 2022

in category: Italian Versions, Craco Pre-Frana Photos, Newsletter Archives, Craco Post-Frana Photos, Craco Society News, Craco Vecchio, Crachesi in America, Holiday, Recipes from Members, Religious Life, A Year in The Life, World War II

Comments Off on April/Aprile 2022 Newsletter – Italian

April/Aprile 2022 Newsletter – English

March 31, 2022

in category: English Versions, Newsletter Archives, Craco Post-Frana Photos, Craco Society News, Craco Vecchio, Crachesi in America, Recipes from Members, Religious Life, A Year in The Life, Uncategorized, World War II, Life in Craco, Craco Today

Comments Off on April/Aprile 2022 Newsletter – English

GAETANO GRIECO AND THE UTOPIA TRAGEDY

On the night of March 17, 1891 one of the most tragic events in Italian immigration history occurred. The consequences of this event on a stormy night 130 years ago are still felt today.

The steamship Utopia was a transatlantic passenger vessel built in 1874 and starting in 1882 she regularily carried Italian immigrants to the United States. To maximize revenue on the Italian route, first class accommodation were reduced, second class was removed, and steerage capacity was increased to 900 bunks.

On February 25, 1891 the Utopia sailed from Trieste for New York City, stopping at Naples, Genoa, and Gibraltar. She carried 880 people including 59 crew, 3 first class passengers, 815 third class passengers, and 3 stowaways. The Utopia normally carried seven lifeboats that could only accommodate 460 people.

Among these passangers was Gaetano Grieco, the ancestor of several Craco Society members. Gaetano was born in Albori, part of the town of Vietri sul Mare in the province of Salerno on March 24, 1860. He was the son of Giuseppe, who was a tailor and Brigida Fiorillo. His birth took place at the home of the then mayor of the town suggesting a connection between the mayor and Gaetano‘s mother (but records supporting that have not been located yet.) Gaetano grew up to become a merchant of fine silk linens and jewels. On April 7, 1882 Gaetano married Giulia Maria Baldasarre in Craco. Giulia was born there on June 26, 1856 to Giovanni and Rosa Maria Matera. Gaetano and Giula settled in Craco where two children were born, Giuseppe (Feb. 13, 1885) and Margarita (Apr. 27, 1887). The family then immigrated to New York City where another daughter, Brigida was born (Feb. 5, 1890).

Grieco family descendants had an oral history of the loss of Gaetano in a shipwreck but lacked full details and understanding about it until recently. With the help of the staff at the Gibraltar Museum the story of Gaetano‘s fate was resolved. The final piece of the puzzle fell into place when Pina Maffoda, a researcher who recovered in archives from Naples, Palermo, and Trieste the names of all the passengers and reconstructed the last voyage of the Utopia.

The Utopia reached Gibraltar on March 17 and navigated to her usual anchorage in the harbor but the location was occupied by two battleships HMS Anson and HMS Rodney.

The Utopia’s captain said he was temporarily blinded by the Anson’s searchlight and “suddenly discovered that the inside anchorage was full of ships”. When attempting to steer Utopia ahead of Anson’s bow a strong gale combined with current swept the vessel across the bows of the Anson, and in a moment her hull was pierced. The impact occurred at 6:36 p.m. and with a hole 16 ft. wide below Utopia’s waterline her holds quickly flooded.

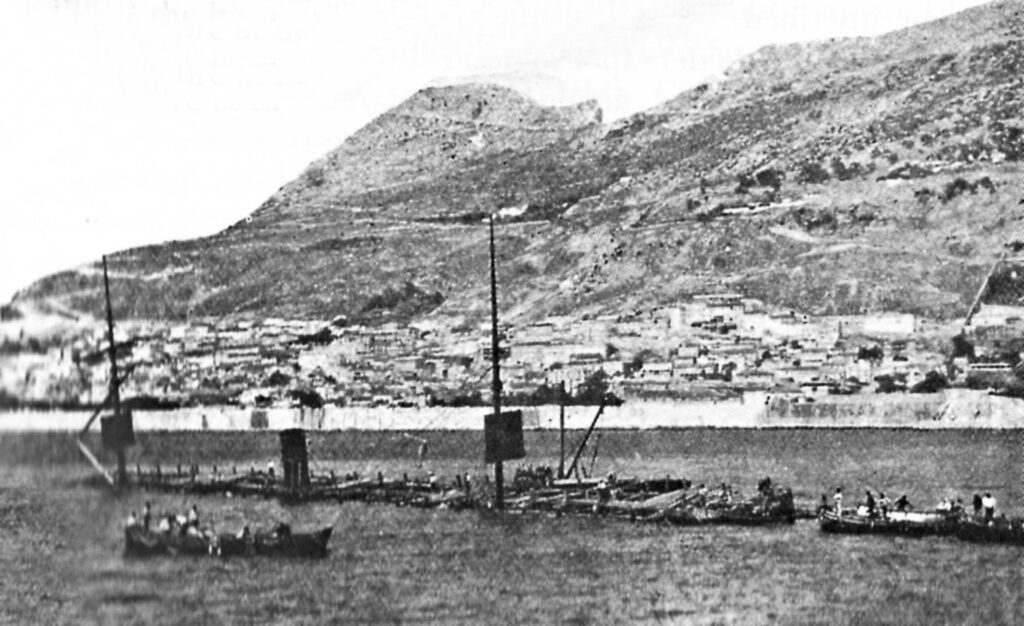

The Utopia’s captain ordered the lowering of the lifeboats and to abandon ship, but Utopia suddenly listed 70 degrees, crushing and sinking the boats. The survivors clung to the starboard of Utopia while hundreds were trapped inside steerage holds but within 20 minutes the Utopia sank. Her masts, protruding above the waves, became the last refuge for survivors.

Nearby ships immediately sent rescue crews to the site, but rough weather and a strong current made it difficult for them to approach the wreck. Rescuers were blinded by the wind and rain but saw a confused, mass of human beings entangled with wreckage. Out of 880 passengers and crew of Utopia, there were 318 survivors: 290 steerage passengers, 2 first class passengers, 3 Italian interpreters, and 23 crew. The remaining 562 passengers and crew were dead or missing.

Divers sent to examine the wreck reported that the inner spaces of Utopia “were closely packed with the bodies … who had become wedged into an almost solid mass”; and that “the bodies of many of the drowned were found so firmly clasped together that it was difficult to separate them.” Hundreds of bodies remained trapped in the steerage holds of the sunken ship.

The Utopia captain was found guilty of grave errors in judgement. After the accident the remains of Utopia were illuminated by lights hoisted on each masthead. However, this did not prevent another incident; the SS Primula, entering the harbor, collided with the wreck of Utopia.

The wreck of Utopia was raised in 1892 and brought to Scotland. It was scrapped in 1900.

Pina Maffoda’s research provided the death record that was sent to Vietri sul Mare. But we do not know how and when Giulia Baldsasarre and her children learned of Gaetano’s death.

The Grieco family knows that after the loss, an uncle who was a professor in Salerno, wanted to educate Giuseppe and raised him there for several years until Giuseppe expressed a desire to return to America to be with his mother and sister.

When he returned to New York City, settling in with the family on Mulberry Street, Giuseppe and his mother started a scrap rag business that evolved into a successful paper stock enterprise. On October 23, 1902 Giuseppe married Maria LoPorchio in Manhattan. She was born in New York to Francesco (b. 1862, Craco) and Giulia Demma (b. 1870, Craco). Giuseppe and Maria would have 11 children that were supported by Giuseppe’s paper stock business. He had several business locations, the last being on West 27th Street in Manhattan, which is now the Selina Chelsea Hotel New York.

Brigida Grieco married Pietro Paduano (b. 1880, Craco) on April 27, 1905 in Craco. Pietro was the son of Giuseppe Paduano (b. 1836, Craco) and Filomena Rinaldi (b. 1846, Craco). Brigida and Pietro immigrated to New York and settled in Brooklyn along with Giuseppe and Maria.

Their many descendants now know how those tragic events so far away occurred.

| The sinking of SS Utopia (March 17, 1891, the Bay of Gibraltar) by Ms. Georgina Smith. Original caption: “sketch by Mrs Georgina Sheriff (courtesy Gibraltar Museum)”. The site operator is Mr. Clive Finlayson, Gibraltar, Director of the Gibraltar Museum. |

Gaetano Grieco e la tragedia dell’utopia

Durante il tardo pomeriggio del 17 marzo 1891 si verificò uno degli eventi più tragici della storia dell’immigrazione italiana. Le conseguenze di quanto accadde, in quel tardo pomeriggio tempestoso di ben 130 anni, sono percepibili ancora oggi.

Utopia era un piroscafo Scozzese costruito nel 1874 ed adibito al trasporto di passeggeri attraverso l’oceano Atlantico. Dal 1882 cominciò a traghettare regolarmente gli immigrati italiani verso le coste degli Stati Uniti. Per massimizzare i profitti sulla rotta italiana, la compagnia gestrice decise di ridurre gli alloggi di prima classe, rimuovendo la seconda classe ed ampliando lo spazio per i passeggeri di terza classe, la cui capacità toccò le 900 cuccette.

Il 25 febbraio del 1891 l’Utopia salpò da Trieste per New York City, facendo scalo anche ai porti di Napoli, di Genova e di Gibilterra. Delle 880 persone che stava trasportando durante quella tratta, 59 erano membri dell’equipaggio, 3 erano passeggeri di prima classe, 815 erano passeggeri di terza classe e 3 erano passeggeri clandestini. L’Utopia era normalmente equipaggiata di sette scialuppe di salvataggio che potevano ospitare fino a 460 persone.

Tra gli 880 passeggeri, c’era anche Gaetano Grieco, un antenato di alcuni membri della Craco Society. Gaetano nacque il 24 marzo 1860 ad Albori, una frazione del comune di Vietri sul Mare in provincia di Salerno in Campania. Era figlio di un sarto di nome Giuseppe e di Brigida Fiorillo. La sua nascita avvenne in quella che era la casa dell’allora sindaco del paese, suggerendo una relazione tra il sindaco e la madre di Gaetano (non sono però ancora stati ritrovati documenti a sostegno di questa tesi). Una volta divenuto adulto, Gaetano si specializzò nella vendita di gioielli di biancheria di seta pregiata.

Il 7 aprile del 1882, Gaetano si unì in matrimonio a Craco con Giulia Maria Baldasarre. Giulia era nata a Craco il 26 giugno del 1856 da Giovanni e Rosa Maria Matera. Gaetano e Giulia si stabilirono a Craco dove ebbero due figli, Giuseppe (nato il 13 febbraio del 1885) e Margherita (nata il 27 aprile del 1887). La famiglia decise di emigrare a New York, dove ebbero un’altra figlia a cui diedero il nome di Brigida (nata il 5 febbraio del 1890).

I discendenti della famiglia dei Grieco erano soliti tramandarsi oralmente il racconto della morte di Gaetano e del suo naufragio. Fino a poco tempo fa non fu però possibile accedere a tutti i dettagli sulla veridicità di questa storia, che rimase spesso incompresa. Grazie all’aiuto dello staff del Museo di Gibilterra, il Gibraltar Museum, è stato possibile approfondire la storia del destino di Gaetano. L’ultimo tassello del puzzle si è risolto grazie al prezioso contributo di Pina Maffoda. Pina è una ricercatrice che, dopo aver ottenuto l’accesso agli archivi di Napoli, di Palermo e di Trieste, è riuscita a recuperare i nomi di tutti i passeggeri che erano a bordo dell’Utopia, potendone ricostruire l’ultimo viaggio.

Una volta raggiunta Gibilterra il 17 marzo del 1891, l’Utopia continuò ad addentrarsi all’interno del porto fino a raggiungere la sua solita area d’ancoraggio. Il destino peró volle che in quel momento fosse occupata dall’HMS Anson e dall’HMS Rodney, due navi da guerra inglesi.

John McKeague, il capitano dell’Utopia, ammise di essere stato temporaneamente accecato dalle luci del riflettore dell’HMS Anson e “scoprì improvvisamente che la sua zona d’ancoraggio del porto era piena di navi”. Non appena il capitano tentò di muovere il timone dell’Utopia per allontanarsi dalla prua dell’HMS Anson, un forte vento di burrasca e la corrente contraria fecero sbattere il piroscafo contro la prua della nave da guerra, causandone la perforazione immediata dello scafo. L’impatto avvenne alle 18:36. Con una fessura larga ben 16 piedi al di sotto della linea di galleggiamento, le stive dell’Utopia si allagarono rapidamente.

Il capitano ordinò a tutti i passeggeri di calare le scialuppe di salvataggio e di abbandonare la nave, ma l’Utopia si inclinò improvvisamente di 70 gradi, schiacciando e facendo sommergere le barche. I sopravvissuti si aggrapparono alla dritta della nave mentre centinaia rimasero intrappolati negli abitacoli di terza classe. In appena 20 minuti l’Utopia si inabissò. I suoi alberi, che si sporgevano sopra le onde, divennero l’ultimo rifugio per i sopravvissuti.

Le navi vicine inviarono immediatamente diverse squadre di soccorso sul sito, ma il maltempo e le forti correnti resero l’avvicinamento al relitto particolarmente arduo. I soccorritori, che dovettero sfidare vento e pioggia, si trovarono davanti ad una massa confusa di esseri umani impigliati nei rottami. Su 880 passeggeri che appartenevano all’equipaggio dell’Utopia, il numero dei sopravvissuti fu appena di 318. 290 passeggeri di terza classe, 2 passeggeri di prima classe, 3 interpreti italiani e 23 membri dell’equipaggio. I restanti 562 passeggeri annegarono durante il naufragio o furono dichiarati dispersi.

I sommozzatori che vennero inviati in seguito per esaminarne quanto rimanesse del relitto riferirono come gli spazi interni dell’Utopia “fossero strettamente stipati con i cadaveri delle vittime … che si erano accatastati gli uni sugli altri quasi a formare una massa solida”; e come “i corpi di molte delle vittime fossero legati insieme così saldamente da rendere difficili le operazioni di perlustrazione”. Centinaia di cadaveri rimasero bloccati negli abitacoli di terza classe della nave affondata.

Il capitano dell’Utopia fu ritenuto colpevole del disastro, causato da gravi errori di giudizio. In seguito all’incidente, i resti dell’Utopia furono illuminati da luci poste sulla punta di ognuno dei suoi alberi per evitare ulteriori disastri. Tuttavia, ciò non fu sufficiente per impedire un altro incidente. Durante la sua entrata nel porto, la SS Primula entrò in rotta di collisione con il relitto del piroscafo.

Il relitto di Utopia fu rimosso dal mare nel 1892 e riportato in Scozia. Venne demolito nel 1900. La ricerca di Pina Maffoda fornisce il verbale sulla morte dei passeggeri, inviato a Vietri sul Mare. Non sappiamo però ancora come e quando Giulia Baldasarre e i suoi figli abbiano appreso della morte di Gaetano.

La famiglia Grieco é al corrente del fatto che, che dopo l’annegamento di Gaetano, uno zio che lavorava come professore a Salerno decise di prendersi cura dell’educazione di Giuseppe. Gli diede l’opportunità di crescere lì per diversi anni fino a quando Giuseppe stesso non espresse il desiderio di ritornare in America e di ricongiungersi con la madre e la sorella.

Una volta rientrato a New York City, stabilendosi con la famiglia su Mulberry Street, Giuseppe e sua madre avviarono un’attività di materiale di rottamazione che progredì con successo come un’impresa commerciale nel settore della raccolta di carta da macero. Il 23 ottobre del 1902 Giuseppe sposò Maria LoPorchio a Manhattan. Maria era nata a New York da Francesco (nato nel 1862 a Craco) e da Giulia Demma (nata nel 1870 a Craco). Giuseppe e Maria ebbero 11 figli che riuscirono a mantenere grazie ai ricavi dell’attività della raccolta della carta di Giuseppe. L’azienda aveva diverse sedi commerciali, di cui l’ultima si trovava sulla West 27th Street a Manhattan, l’attuale Selina Chelsea Hotel di New York.

Sappiamo che Brigida Grieco si sposò a Craco con Pietro Paduano (nato nel 1880 a Craco) il 27 aprile del 1905. Pietro era figlio di Giuseppe Paduano (nato nel 1836 a Craco) e Filomena Rinaldi (nata nel 1846 a Craco). Brigida e Pietro emigrarono a New York e si stabilirono a Brooklyn assieme a Giuseppe e Maria.

I loro numerosi discendenti sono ora al corrente di come si verificarono quei tragici eventi.

.

May 28, 2021

in category: Crachesi in America, Genealogy

Tagged SS Utopia, Gaetano Grieco

Comments Off on GAETANO GRIECO AND THE UTOPIA TRAGEDY

GAETANO GRIECO AND THE TWIST OF FATE

Last month’s Newsletter article triggered a memory from another Society member that shows us how a twist of fate can impact us and influence generations.

The amazing story from Joe Rinaldi of Rhinebeck, New York, adds depth to our understanding of how and why Gaetano Grieco was aboard the SS Utopia when it and he met tragic ends 130 years ago in Gibraltar Harbor. Joe Rinaldi related the following story.

“…this story was told to me by my {maternal} grandmother Anna (DiDonato) Miele (1897-1986).

Anna’s parents, Antonio DiDonato (1869-1917) and Giuseppina (Brescia) DiDonato (1872-1951) [who were from Avellino, in the Campagna Region] were to travel in 1891 from Avellino with a friend who was a businessman, dealing between Italy and the US, who would help settle my great grandparents in New York City when they all arrived.

Just before they were to board the ship, the friend had a business situation come up, so he told my great grandparents to go ahead and he would take the next ship and meet them in New York.

Either while still making the passage or once arriving in New York, Giuseppina and Antonio learned of the sinking of the SS Utopia at Gibraltar and the loss of their friend.

Fortunately for my great grandparents, they knew the name of their friend’s business contact in New York City, so they got in touch with him and he was able to help Giuseppina and Antonio get a place to live and a job for Antonio, who was a carpenter.”

So, we now know that a simple thing like the innocent business meeting Gaetano attended was the twist of fate that changed his destiny.

Che sarà sarà.

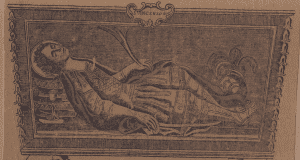

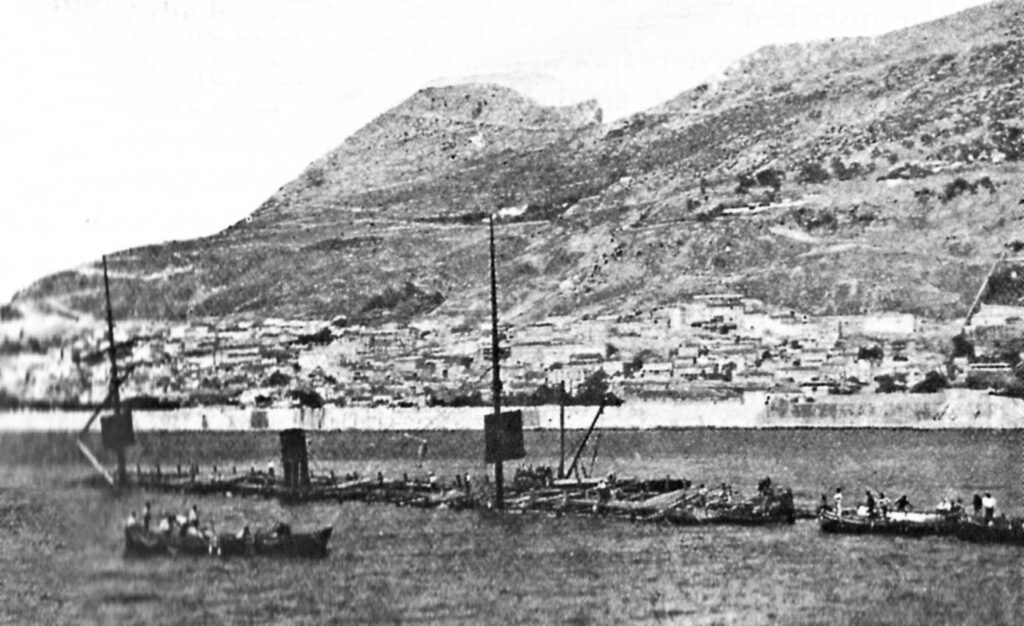

| HMS Anson and SS Utopia—The contemporary sketch above, shows the HMS Anson (right) using a searchlight to illuminate the sinking SS Utopia (left). The HMS Anson, had a battering ram in her bow ,which was struck by the Utopia as she passed the ship at 6:36pm during the stormy night of March 17, 1891. The Utopia, with a 16 foot wide gash in her hull sank within 20 minutes. Of the Utopia’s 880 passengers, mostly Italian immigrants, 562 were lost. The Utopia’s captain, John McKeague was found guilty of grave errors in judgement: “firstly, in attempting to enter the anchorage … without having first opened out and ascertained what vessels were there” and “secondly, in attempting to turn his ship out across the bows of HMS Anson. Sunken Utopia— shown below is the sunken SS Utopia in Gibraltar Harbor. This contemporary photograph . Work crews, barges and lighters are visible on the wreck. The square objects on the masts were markers to help prevent other ships from colliding with the wreck. The Utopia was raised in July 1892 and brought to Scotland where the hulk was scrapped in 1900. |

GAETANO GRIECO E UNO SCHERZO DEL DESTINO

L’articolo su Gaetano Grieco che abbiamo condiviso all’interno dell’aggiornamento del mese scorso ha risvegliato la memoria di un altro membro della Craco Society, il cui racconto ci mostra come uno scherzo del destino può avere un’incredibile influenza sulla nostra vita e quella delle generazioni future.

La storia inverosimile di Joe Rinaldi di Rhinebeck, a New York, ci aiuta ad approfondire e a capire meglio come e perché Gaetano Grieco si trovasse a bordo della SS Utopia nel momento del suo tragico affondamento nel porto di Gibilterra, circa 130 anni fa.

Joe Rinaldi ha condiviso con noi i dettagli dell’avvenimento.

“… questa storia mi è stata riferita da mia nonna {materna} Anna (DiDonato) Miele (1897-1986).

I genitori di Anna, Antonio DiDonato (1869-1917) e Giuseppina (Brescia) DiDonato (1872-1951) [che erano originari di Avellino, un paese della Regione Campania] lasciarono da Avellino per andare in America nel 1891. Con loro si trovava un certo amico e uomo d’affari, il quali era solito gestire trattative commerciali tra l’Italia e gli Stati Uniti. Quest’Amico [che in realtà non era che Gaetano Grieco] avrebbe avuto il compito di aiutare i miei bisnonni a sistemarsi a New York City una volta sbarcati negli Stati Uniti. Poco prima che salissero a bordo, l’amico fu improvvisamente costretto ad assentarsi e a ritardare la propria partenza a causa di un incontro di lavoro. Lui disse quindi ai miei bisnonni di andare avanti e che si sarebbe imbarcato sulla nave successiva e li avrebbe incontrati direttamente a New York.

Mentre erano ancora in viaggio durate la traversata oceanica o una volta sbarcati a New York, Giuseppina e Antonio vennero a sapere del naufragio della SS Utopia a Gibilterra e della morte del loro amico.

Fortunatamente per loro, i miei bisnonni conoscevano il nome del socio d’affari del loro amico a New York City. Riuscirono a mettersi in contatto con questa persona, la quale fu in grado di aiutarli a trovare un posto dove vivere e un impiego per Antonio, che faceva il falegname.”

Sappiamo ora che una cosa banale come un innocente e improvviso incontro di lavoro a cui Gaetano dovette partecipare rappresentò per lui un vero e proprio scherzo del destino che cambiò per sempre le sue sorti.

Che sarà sarà.

| HMS Anson e SS Utopia: il quadretto in alto, realizzato in età contemporanea, mette in mostra l’HMS Anson (visibile sulla destra) ed il riflettore utilizzato per illuminare il naufragio della SS Utopia (visibile sulla sinistra). L’HMS Anson aveva un ariete a prua, che entrò in contatto con l’Utopia quando questa le passó davanti alle 18:36 del tardo pomeriggio tempestoso del 17 marzo 1891. Con uno squarcio largo 16 piedi (quasi cinque metri) nello scafo, l’Utopia affondò nel giro di 20 minuti. Degli 880 passeggeri che si trovavano a bordo, per lo più emigranti italiani che si stavano dirigendo verso gli Stati Uniti, 562 annegarono. John McKeague, il capitano dell’Utopia, fu ritenuto colpevole a causa di gravi errori di giudizio. Due furono le accuse principali. “In primo luogo, John McKeague tentò di effettuare le operazioni di ormeggio…senza però aver prima dichiarato la propria posizione e senza essersi accertato di quali altri navi fossero già in porto”. “In secondo luogo, cercò di effettuare un cambio di direzione attraverso la prua della HMS Anson.” Il relitto dell’Utopia — in una fotografia contemporanea in basso, è possibile osservare la SS Utopia dopo il suo naufragio presso il porto di Gibilterra. Sopra ciò che rimane dell’imbarcazione sono visibili squadre operative, chiatte e luci per facilitare i lavori. Gli oggetti quadrati sugli alberi della nave non erano altro che indicatori posizionati lì proprio come segnale e per aiutare altre navi a non entrare in collisione con il relitto. I residui dell’Utopia furono levati dal mare nel luglio del 1892 e riportati in Scozia, dove vennero completamente demoliti nel 1900. |

May 25, 2021

in category: Crachesi in America, Genealogy

Tagged SS Utopia, Gaetano Grieco

Comments Off on GAETANO GRIECO AND THE TWIST OF FATE

ITALIAN SURNAME ORIGINS

After learning about the historic surnames from Craco it became obvious understanding their origins would be important.

Onomatology is the study of the origins and history of proper names. There are two works that help us identify the roots of the Cracotan names. Prof. Joseph G. Fucilla wrote, Our Italian Surnames, in 1949 and has been in print since then because of its extensive coverage of the subject. In 1985, Gerhard Rohlfs wrote, Dizionario storico dei cognomi in Lucania, an Italian language publication containing an extensive listing of regional surnames. Fucilla and Rohlfs explain Italian surnames came from several sources and that they were adopted in the last 400 years.

Through most of history a single given name was the standard. The Romans began adding a “gens-name” derived from the founder of the family tree. The early Christians and Germanic tribes, both used single given names and they caused the collapse of the Roman naming system. However, between these two groups the hereditary surname system universally used today slowly emerged.

Starting with the patricians in Venice about the 9th century it took another 800 more years for surnames to take root.

The pattern of Italian surnames originally relied on expressing paternity (for example, Giovanni di Alberto representing Giovanni son of Alberto). These were influenced over time by various factors. For example the singular surname became plural reflecting the family that the surname came from (Alberto becomes Alberti.) Another way of expressing “son of” (figlio) also emerged by using the prefix —Fi or Fili (examples, Fittipoldi, Filangieri).

The many groups who invaded Italy also added to the surname development process. Greek, Roman, and Germanic influence are seen as the major source of Italian surnames with a secondary set attributed to Hebrew names.

Greek roots are seen in names like Alessandri, or Greek with the Christian influence like Basilio. Roman examples are numerous and include classical names like Caesar. The Germanic Franks and Lombards while abandoning their native language retained their Teutonic names. These can be recognized with surname endings like –aldo (example Rinaldi), or -mano (Germano). Hebrew names derived from the Bible include Salomone and Vitelli (from David).

Adding to the complex evolution of surnames were other elements that became name sources including desirable or undesirable qualities, botanical, topographical, geographic, animal, anatomical, objects and occupations. Also, in the regional areas of rural Italy each family had a nickname which was transmitted to subsequent generations. Over centuries and generations additional modifications give us the names we recognize today.

CRACOTAN SURNAME ORIGINS

Avena— botanical, representing oat farmer (Fucilla)

Basilio—of Greek origin (Rohlfs & Fucilla)

Benedetto—compound surname (Fucilla)

Bentivenga—from Moliterno, indicating good feelings (Rohlfs); may good befall you (Fucilla)

Branda—French origins (Rohlfs)

Camberlengo—French origins (Rohlfs)

Colabella—attractive physique (Fucilla)

Conte—reflecting a title (Rohlfs); titular name origin, count (Fucilla)

Cotugno—botanical name, quince (Fucilla)

DeCesare—from Roman, of Cesear (Fucilla)

Dolcemiele— compound surname, sweet honey (Fucilla)

Donadio—indicating good feelings (Rohlfs); biblical origin, given by and to God (Fucilla)

Episcopio—from ecclesiastical name, bishop (Fucilla)

Gallo—Spanish origins (Fucilla)

Grieco—Greek nationality (Rohlfs)

Laino—geographic origin (Rohlfs)

Lorubbio—from Craco, Montalbano Jonico, Policoro (Rohlfs); derived from hair color, red (Fucilla)

Lospinuso—from Craco, Montalbano Jonico (Rohlfs); originated as a nickname, full of thorns, harsh(Fucilla)

Magistro—name for learned men, teacher (Fucilla)

Mastronardi—reflecting a title (Rohlfs); formed from master of and the baptismal name (Fucilla)

Muzio—from Sala Consilina, Salerno (Rohlfs); derived from Spanish, stable boy (Fucilla)

Pignataro-from Potenza, (Rohlfs), occupation name, potter (Fucilla)

Pirretti—from Ferrandina Matera (Rohlfs); derived from the given name Pietro (Fucilla)

Ragone—Spanish origin (Rohlfs)

Roccanova—from Potenza, Matera derived from agriculture (Rohlfs)

Rinaldi—Germanic origin (Rohlfs), from the legendary knight Roland (Fucilla)

Salamone—reflecting a distinguished person (Rohlfs); from the Bible, Solomon, a wise person (Fucilla)

Spera—from Matera, person which raises hope (Rohlfs)

Tuzio—from Lagonegro, Montalbano, Sapri, and Senise, from medieval name Tutius (Rohlfs)

Veltri—derived from the dog breed of greyhounds (Fucilla)

Viggiano—from Matera, Montablano, Potenza, Stigliano (Rohlfs)Vitelli—derived from the Biblical name David (Fucilla)

An online source of Italian surname history is available at: ORIGINI DI COGNOMI ITALIANI

LE ORIGINI DEI COGNOMI ITALIANI

Dopo aver appreso quelli che sono i cognomi italiani di Craco è diventato ovvia l’importanza di capire le loro origini.

L’Onomatologia rappresenta lo studio dell’etimologia e della storia dei nomi propri. Ci sono due studi disponibili che ci permettono di identificare le radici dei nomi crachesi. Prof. Joseph G. Fucilla scrisse nel 1949 “I nostri cognomi Italiani” (Our Italian surnames in inglese), testo tuttora in stampa proprio grazie al livello di dettaglio con cui descrive il tema. Nel 1985 Gerhard Rohlfs preparò invece un “dizionario storico dei cognomi lucani, una pubblicazione in lingua italiana contenente una lista estesa di cognomi regionali. Fucilla e Rohlfs spiegano come diverse siano state le fonti e le ragioni nella formazione dei cognomi italiani adottati negli ultimi 400 anni.

Storicamente, la maggior parte dei nomi propri erano composti da un nome unico. I romani cominciarono ad aggiungere un “nome gens”, quindi il nome derivante dal fondatore dell’albero genealogico famigliare. I primi cristiani, così come le tribù germaniche, usavano i nomi propri singoli e sostituirono il proprio sistema a quello romano, creando un collasso di quest’ultimo.

In ogni caso, tra queste due metodistiche quella del cognome ereditario come viene usato ora universalmente non era ancora emersa.

Fu infatti nel nono secolo dopo cristo con i patrizi a Venezia che l’attuale sistema cominciò ad ampliarsi, il cui sviluppo durò circa 800 anni o più prima di ottenere la comformazione attuale.

La forma con cui i cognomi italiani erano costruiti originalmente rispecchia il legame paterno (per esempio, “Giovanni di Alberto” significa “Giovanni figlio di Alberto”). Diversi sono poi i fattori che nel tempo ne hanno modificato l’assetto. Per esempio, molti nomi singolari hanno assunto una forma plurale e sono rimasti tali, identificando in questo modo il nome famigliare (per esempio “Alberto” diventerebbe “Alberti”). Un’altra maniera di esprimere il termine di “figlio” era rappresentata dall’uso del prefisso “Fi” oppure “Fili” (alcuni esempi sono “Fittipoldi” o “Filangeri”).

Anche i diversi eserciti e le popolazioni che invasero l’Italia parteciparono al processo di sviluppo dei cognomi famigliari. Le influenze greche, romane e germaniche sono quelle che hanno maggiormente pesato sui cognomi italiani di derivazione ebrea.

Radici greche sono riscontrate in nomi come “Alessandri”, oppure radici greche con un influenza cristiana, come per esempio “Basilio”. Gli esempi di varianti romane sono molteplici ed includono nomi come “Cesare”. I franchi-tedeschi ed i lombardi hanno assunto nomi teutonici, abbandonando il loro linguaggio nativo. Possono essere riconosciuti poichè terminano con –aldo (per esempio “Rinaldi”) o –mano (“Germano”). I nomi ebrei che hanno radici bibliche includono Salomone e Vitelli (da “Davide”).

Oltre all’evoluzione già di per sè complessa della natura di un nominativo, ci sono altri elementi da considerare che hanno assunto nel tempo un certo livello di influenza. Questi includono qualità desiderabili o indesiderabili, elementi legati al mondo botanico, topografico, geografico, animale, anatomico, oggetti così come impieghi. Oltre a ciò, nelle regioni rurali italiane ogni famiglia aveva un proprio soprannome, il quale veniva trasmesso di generazione in generazione. Durante i secoli e a causa del susseguirsi delle generazioni stesse, ulteriori modifiche hanno aiutato a modificare i nostri nomi fino a diventare quelli che sono oggi.

LE ORIGINI DEI COGNOMI CRACHESI

Avena—dal mondo botanico, rappresentante dei contadini di avena (Fucilla)

Basilio—di origine greca (Rohlfs & Fucilla)

Benedetto—nome composto (Fucilla)

Bentivenga—da Moliterno, indicatore di buone sensazioni (Rohlfs); che il bene possa essere con te (Fucilla)

Branda—di origini francesi (Rohlfs)

Camberlengo— di origini francesi (Rohlfs)

Colabella— dal fisico attraente (Fucilla)

Conte— che riflette il titolo nobiliare (Rohlfs); nome di un titolo, conte (Fucilla)

Cotugno—nome di origine botanica, mela cotogna (Fucilla)

DeCesare— dal nome romano, di Cesare (Fucilla)

Dolcemiele— nome composto, dolce e miele (Fucilla)

Donadio—che indica sensazioni piacevoli (Rohlfs); di origine biblica, dato da e per Dio (Fucilla)

Episcopio—nome d’origine ecclesiastica, vescovo (Fucilla)

Gallo—nome d’origini spagnole (Fucilla)

Grieco—nazionalità greca (Rohlfs)

Laino— di origini geografiche (Rohlfs)

Lorubbio—da Craco, Montalbano Jonico, Policoro (Rohlfs); derivante dal colore rosso carota dei capelli (Fucilla)

Lospinuso—da Craco, Montalbano Jonico (Rohlfs); in origine come soprannome, pieno di spine, duro(Fucilla)

Magistro—nome di persona acculturata, maestro (Fucilla)

Mastronardi—che riflette un titolo (Rohlfs); creato per uno specialista in un arte, nome di battesimo (Fucilla)

Muzio—dalla Sala Consilina, Salerno (Rohlfs); derivante dallo spagnolo, ragazzo di stalla (Fucilla)

Pignataro-da Potenza, (Rohlfs), nominativo di occupazione, ceramista (Fucilla)

Pirretti—da Ferrandina Matera (Rohlfs); derivante dal nome proprio Pietro (Fucilla)

Ragone—di origine spagnola (Rohlfs)

Roccanova—da Potenza e Matera, deriva dall’agricoltura (Rohlfs)

Rinaldi— di origini germaniche (Rohlfs), dal cavaliere leggendario Rolando (Fucilla)

Salamone—riflette una persona di qualità distinte (Rohlfs); dalla Bibbia, Salomone, uomo saggio (Fucilla)

Spera—da Matera, persona che porta speranza (Rohlfs)

Tuzio—da Lagonegro, Montalbano, Sapri, e Senise, derivante dal nome medievale Tutius (Rohlfs)

Veltri—derivante dall’allevamento di cani levrieri (Fucilla)

Viggiano—da Matera, Montablano, Potenza e Stigliano (Rohlfs)

Vitelli—derivante dal nome biblico Davide (Fucilla)

Una fonte storica di cognomi italiani è disponibile su: ORIGINI DEI COGNOMI ITALIANI

May 21, 2021

in category: Craco Vecchio, Crachesi in America, Genealogy

Tagged Italian Surnames, Cracotan Names

Comments Off on ITALIAN SURNAME ORIGINS

THE DOCTOR FROM CRACO

Dr. Donato Viggiano, the doctor from Craco appeared in several Newsletter articles including in April 2020, July 2014, and March 2012.

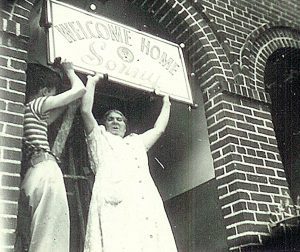

This appearance was prompted by a new photograph sent by Society member Annette Benedetto from her college graduation celebration in 1961.

In 1903, the then 27 year old doctor, Donato Viggiano arrived in New York from Craco and began helping the immigrant community on the Lower East Side. Obviously, coming from Craco he was preferred by his Cracotan “paesani” providing for them and other immigrants from his office at 76 Mott Street. In 1912, he married Elvira Manghise and they established a home in Brooklyn.

Dr. Viggiano crossed paths with Mother Cabrini early in his career and supported her by caring for the ill. While continuing his work on the Lower East Side and attending to the immigrant community there he also worked with the Columbus Hospital that Mother Cabrini founded, ultimately taking on an administrative role there. In the 1930s he and his wife were regularly listed in newspapers as sponsors promoting fund raising events and activities aimed at supporting the hospital during the Depression.

Dr. Viggiano continued practicing medicine into the 1950s and passed away in 1972 at the age of 95.

His impact on the Cracotan community in New York was significant. Families who had ancestors in Little Italy in his era have stories about their interactions with him.

Cracotan Physician—Dr. Donato Viggiano (shown above in a 1924 passport photograph) was a fixture in Little Italy and preferred by his Cracotan paesani because of his ability to speak the dialect. He ultimately became an administrator of Columbus Hospital in Manhattan that was founded by Mother Cabrini. Also pictured is his eleven year old daughter Rosina and wife Elvia who traveled with him that Summer to France and Italy. They left New York on July 10th aboard the SS Albania and returned October 11th from Naples aboard the steamship Conte Rosso. Dr. Viggiano and his wife made trips back to Italy in the ensuing years with visits in 1948 and 1956.

——-

Un medico Crachese — Il dottor Donato Viggiano (immortalato in alto in una fotografia da passaporto del 1924) diventò una figura di riferimento a Little Italy, essendo preferito dai suoi paesani Crachesi per la sua capacità di comunicare in dialetto. Alla fine della sua carriera coprì un ruolo amministrativo nel Columbus Hospital di Manhattan, fondato da Madre Cabrini. Nella foto é visibile anche Rosina, la figlia di undici anni, ed Elvira, sua moglie, le quali lo accompagnarono durante il viaggio dell’estate del 1924 in Francia e in Italia. Salparono il 10 luglio da New York a bordo della SS Albania e ripartirono da Napoli verso l’America l’11 ottobre a bordo del piroscafo Conte Rosso. Il dottor Viggiano e sua moglie completarono diversi viaggi in Italia negli anni seguenti, con due visite principali nel 1948 e nel 1956.

Elvira e Dr. Donato Viggiano 1939.

Elvira (destra) e Dr. Donato Viggiano (sinestra) 1961.

_________

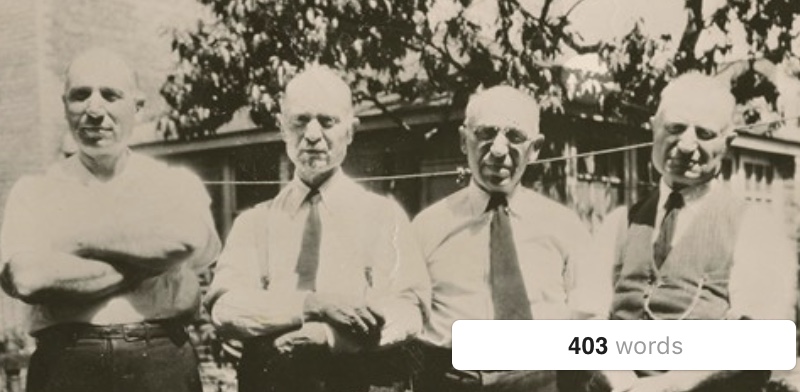

I Fratelli Viggiano – Donato, Prospero, Antonio (soprannominato “Giudice”) e Antuono (soprannominato “Tony”) sono visibili in basso sulla sinistra. Donato, di professione medico, e Prospero, di professione barbiere, risiedevano entrambi a Manhattan e rappresentavano figure portanti all’interno della comunità crachese.

IL DOTTORE DA CRACO

Il medico di Craco Donato Viggiano è apparso in diversi articoli dei nostri aggiornamenti mensili, tra cui anche quelli di Aprile 2020, Luglio 2014 e Marzo 2012.

Il suo riferimento è dovuto ad una nuova fotografia condivisa dal membro della Craco Society Annette Benedetto e risalente al momento di celebrazione della laurea di Annette stessa, 1961.

Nel 1903 il medico Donato Viggiano arrivò a New York ad appena 27 anni d’età. In quel periodo iniziò ad aiutare la comunità di immigrati del Lower East Side. Grazie alle sue origini Crachesi, il dottor Viggiano era altamente preferito dai suoi paesani che visitava assieme agli immigrati di altri paesi nel suo ufficio di Mott Street 76. Nel 1912 sposò Elvira Manghise prima di stabilirsi con lei in una casa di Brooklyn.

All’inizio della sua carriera, il dottor Viggiano incontrò diverse volte Madre Cabrini e la sostenne prendendosi cura degli infermi. Sempre continuando a lavorare nel suo ufficio del Lower East Side e frequentando la comunità di immigrati della zona, il dottor Viggiano lavorò anche con il Columbus Hospital fondato da Madre Cabrini, in cui alla fine assunse un ruolo amministrativo.

Negli anni trenta il dottor Viggiano era regolarmente menzionato assieme alla moglie sui giornali come sponsor poiché promuoveva eventi e attività di raccolta fondi atti a sostenere l’ospedale durante il periodo della grande depressione.

Il dottor Viggiano continuò a praticare come medico negli anni cinquanta e morì nel 1972 all’età di ben 95 anni.

Il suo impatto sulla comunità Crachese di New York fu senza alcun dubbio significativo. Molte famiglie che vivevano a Little Italy in quell’epoca parlano ancora delle storie e degli incontri che i loro antenati ebbero con lui.

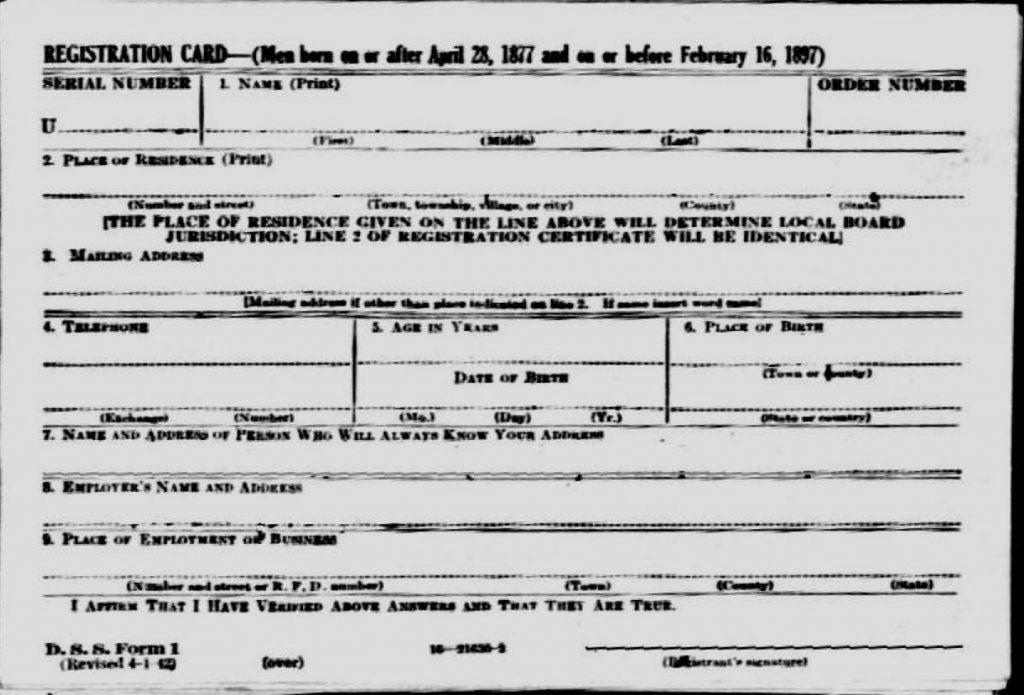

World War II – Selective Service Act

After the U.S. entered WWII a new selective service act required that all men between ages 18 and 65 register for the draft. Between November 1940 and October 1946, over 10 million American men were registered.

World War II – The Fourth Registration

The Ancestry.com database is an indexed collection of the draft cards from the Fourth Registration, the only registration currently available to the public (the other registrations are not available due to privacy laws). The Fourth Registration, often referred to as the “old man’s registration,” was conducted on 27 April 1942 and registered men who born on or between 28 April 1877 – 16 February 1897 – men who were between 45 – 64 years old – and who were not already in the military.

This list is an extract from the Ancestry.com database based on a search using “Craco, Matera Italy” as the input criteria. The images of these cards are available online at the Ancestry.com website and can be downloaded.

Information available on the draft cards includes:

• Name of registrant

• Age

• Birth date

• Birthplace

• Residence

• Employer information

• Name and address of person who would always know the registrant’s whereabouts

• Physical description of registrant (race, height, weight, eye and hair colors, complexion)

Additional information such as mailing address (if different from residence address), serial number, order number, and board registration information may also be available.

For individuals who lived near a state border, sometimes their Draft Board Office was located in a neighboring state. Therefore, you may find some people who resided in one state, but registered in another.

The collection of records at Ancestry.com is incomplete due to data entry backlog or missing records from some states. Therefore, it is possible that an ancestor, who fits the age requirement of this registration, will not currently be found in this database. Records for additional states will be added to this database as Ancestry can acquire them.

| Name | Birth Date | Residence |

| Vincenzo Andrisano | 27 Apr 1888 | Brooklyn, New York |

| Anthony Basilio | 17 Feb 1881 | Kings, New York |

| Vincenzo Benedetto | 11 Sep 1886 | Kings, New York |

| Lorenzo Branda | 10 Oct 1885 | New York, New York |

| Antonio Camperlengo | 27 Oct 1886 | Queens, New York |

| Nicholas P Caricato | 13 Dec 1883 | Hudson, New Jersey |

| Dominick Colabella | 17 Sep 1891 | Kings, New York |

| Francesco Colabella | 17 Jan 1879 | Brooklyn, New York |

| Frank Colabella | 19 Apr 1894 | Brooklyn, New York |

| Joseph Conte | 25 Jul 1892 | Brooklyn, New York |

| Vincent Decostole | 4 Jan 1890 | Staten Island, New York |

| Dominick Demarco | 1 Nov 1896 | New York, New York |

| Nicola Digiovanni | 29 Sep 1885 | New York, New York |

| Anthony Donadio | 16 Jun 1889 | Kings, New York |

| Giuseppe Donnaddi | 16 Oct 1882 | Kings, New York |

| Leonard Episcopio | 24 Oct 1890 | Brooklyn, New York |

| Charles Ferrando | 5 Jun 1895 | New York, New York |

| Pasquale Fezza | 9 Dec 1883 | Queens, New York |

| Nicholas Francavilla | 23 Jun 1895 | Brooklyn, New York |

| Antonio Frumento | 9 Mar 1893 | Kings, New York |

| Frank Frumento | 24 Oct 1987 | Brooklyn, New York |

| Antonio Gaetano | 18 Jun 1885 | New York, New York |

| Ambrose Galante | 18 Jan 1888 | Kings, New York |

| Vincenzo Gallo | 12 Oct 1889 | Manhattan, NY |

| Pasquale Anthony Gesualdi | 8 Sep 1890 | Bucks, Pennsylvania |

| James Gesualdo | 6 Nov 1892 | Kings, New York |

| Peter Vincent Grecco | 27 Dec 1890 | Kings, New York |

| Egidio Grezzi | 1 Jul 1887 | Kings, New York |

| Leonardo Grieco | 19 Feb 1882 | New York, New York |

| Salvatore Grieco | 24 May 1891 | Kings, New York |

| Nicolangelo Grossi | 25 Jan 1885 | Hudson, New Jersey |

| Giacomo Grossi | 22 Jun 1892 | Kings, New York |

| Nicola Jacovino | 10 Nov 1881 | New York, New York |

| LaRubbio Joseph | 18 Oct 1881 | Kings, New York |

| Joseph Laviera | 2 Sep 1888 | New York, New York |

| Vincent James Lombardi | 17 Aug 1895 | Queens, New York |

| Peter A. Manfredi | 27 Mar 1894 | Queens, New York |

| Andrew Manghise | 31 Oct 1884 | New York, New York |

| Anthony Manghise | 16 Nov 1891 | Corona, New York |

| Joseph Manghise | 11 Mar 1891 | New York, New York |

| Andrew Marmo | 21 Mar 1890 | New York, New York |

| Frank Maronna | 19 Nov 1884 | Brooklyn, New York |

| Amedeo Marrese | 18 Dec 1879 | Queens, New York |

| John Mastrangelo | 17 Nov 1887 | New York, New York |

| Charles A Mastronardi | 14 Dec 1896 | Kings, New York |

| Nicholas Mastronardi | 16 Jan 1894 | Hartford, Connecticut |

| Joseph Anthony Mastronardi | 13 Oct 1880 | Hudson, New Jersey |

| Daniel Patrick Matera | 22 Jan 1897 | Kings, New York |

| Dominick J Matera | 23 Jan 1893 | Kings, New York |

| James Matera | 21 Jul 1885 | Kings, New York |

| Joseph Giuseppe Mormando | 17 Jul 1883 | Kings, New York |

| Michael Mormando | 20 Sep 1890 | Kings, New York |

| Nicholas Mormando | 19 Mar 1896 | Kings, New York |

| Pietro Padovano | 12 Jun 1880 | Kings, New York |

| Angelo Ralph Paduani | 1 Nov 1881 | Middlesex, New Jersey |

| Pasquale Vincenzo Palmieri | 28 Sep 1882 | Brooklyn, New York |

| Pasquele Parziale | 15 Nov 1879 | New York, New York |

| Thomas Pascariello | 25 Feb 1888 | Kings, New York |

| Rocco Perretti | 22 Sep 1888 | Kings, New York |

| Antonio Prisco | 18 Jan 1893 | New York, New York |

| Giuseppe Rinaldi | 11 Jul 1884 | Brooklyn, New York |

| Leonardo Antonio Rinaldi | 22 Jan 1891 | Queens, New York |

| Peter Rinaldi | 8 Dec 1884 | Kings, New York |

| Pietro Rubertone | 16 Sept 1873 | New York, New York |

| Vitantonio Rubertone | 17 May 1887 | New York, New York |

| Frank Roccanova | 12 Apr 1895 | New York, New York |

| Joseph Sarubbi | 16 Jul 1894 | Hudson, New Jersey |

| Michael A Sellare | 29 Jun 1894 | New York, New York |

| Anthony Sellaro | 31 Jan 1892 | Kings, New York |

| Peter Serafin | 29 Jan 1886 | New York, New York |

| Carlo Simonetti | 9 Sep 1889 | Bronx, New York |

| Dominick Anthony Spero | 15 Jan 1883 | Queens, New York |

| Frank J Spero | 7 Jun 1886 | Kings, New York |

| Frank Tocci | 27 Apr 1877 | Camden, New Jersey |

| Joseph Tuzio | 22 Sep 1890 | Kings, New York |

| Prospero Tuzio | 9 Sep 1893 | Hudson, New Jersey |

| Frank Vitarello | 16 Apr 1878 | Kings, New York |

| Joseph Viverito | 2 Aug 1885 | New York, New York |

| Nicola Zaffarese | 7 Mar 1883 | New York, New York |

May 31, 2017

in category: Crachesi in America

Tagged WWII Fourth Registration, WWII Old Man's Registration, Italians in WWII

Comments Off on World War II – The Fourth Registration

San Vincenzo’s Tailor

After the completion of the 112th Feast of San Vincenzo in New York City the story of how the statue at St. Joseph’s Church was made surfaced. This story ends speculation about the origins of the statue and perhaps provides insight into how the banner from the Societá San Vincenzo Martire di Craco was made.

Rosa D’Elia Francavilla shared a story about her great grandfather Pasquale Marrese making the clothing for the statue. Rosa’s mother, Maria Teresa Tuzio was the daughter of Giuseppe Tuzio and Rosa Marrese who were married in Craco in 1902. Rosa Marrese’s father, Pasquale Marrese (Born 1846 Craco, died 1914 Jersey City, NJ) had emigrated to the US in the 1880s was a mainstay of the Crachesi community in New York City. Pasquale brought his tailoring skills to America and established a shop at 53 Spring St., Manhattan. He also encountered both tragedy and also success as one of the founders of the Societá San Vincenzo Martire di Craco an organization he helped create to aid his paesani immigrants. As an incorporator and Director of the Societá in 1899 he set a course for the organization that would support the Cracotan community in New York for the next 50 years.

By 1899, he had moved his household from 221 Mulberry St. to Jersey City, NJ but continued to maintain his tailor shop in New York. In 1901 when the Societá San Vincenzo Martire di Craco entered into a contract with St. Joachim’s Church to provide a statue of San Vincenzo and a relic of the saint, considerable coordination and work was required. This may explain why it took two years from the organization’s founding to arrange to install the statue and relic in the church. Pasquale Marrese’s role becomes even more important as we learn from his great-granddaughter that he was responsible for sewing the clothing on the statue in New York. It makes great sense that a Crachese, with tailoring skills would be involved in creating the statue of San Vincenzo in New York in 1900. Relying on his memory of the statue’s clothing in Craco and perhaps the woodcut of the saint that was brought to America by the immigrants he lovingly fabricated the statue’s intricate and bejeweled clothing. More than likely he also created the statue’s body using a mannequin. With the extensive detail some of the work was also done by fellow Cracotans who were employed at his shop.

il Sarto di San Vincenzo

Al termine della 112esima festa di San Vincenzo nella città di New York, è emersa la storia di come la sua statua risucì ad arrivare nella chiesa di St Joseph. Questo racconto pone fine alle varie speculazioni sulle origini della statua, fornendo una traccia informativa importante anche sulla creazione del manifesto della Societá San Vincenzo Martire di Craco.

Rosa D’Elia Francavilla ha iniziato a spiegare la storia di come suo nonno, Pasquale Marrese, ha filato il tessuto per la statua. La madre di Rosa, Maria Teresa Tuzio, era la figlia dei coniugi Giuseppe Tuzio e Rosa Marrese, uniti in matrimonio a Craco nel 1902. Il padre di Rosa Marrese, Pasquale Marrese (nato nel 1846 a Craco e morto nel 1914 a Jersey City, nello stato del New Jersey) emigrò negli Stati Uniti nei tardi anni ottanta del diciannovesimo secolo: durante la sua vita avrebbe rappresentato un pilastro importante della comunità crachese di New York City.

Pasquale riuscì a replicare le proprie abilità sartoriali in America, creando una sua bottega su Spring Street 53 a Manhattan. Attraversò diversi momenti tragici ma anche di successo come fondatore della Societá San Vincenzo Martire di Craco, organizzazione che lui aiutò a formare per aiutare e dare supporto agli altri paesani immigrati. Come fondatore e direttore della Societá, nel 1899 delineò una struttura organizzativa che avrebbe garantito un sostegno alla comunità crachese di New Yok per i 50 anni successivi.

Nel 1899 traslocò nella sua nuova dimora di Mulberry Street 221 a Jersey City, stato del New Jersey, mantenendo però il suo negozio a New York. Nel 1901, quando la Societá San Vincenzo Martire di Craco firmò un contatto con la chiesa di St. Joachim per dare in custodia la statua di San Vincenzo e la sua reliquia, fu necessaria una buona dose di lavoro e coordinazione. Questo spiega in parte il motivo per cui furono necessari ben due anni per l’organizzazione prima di riuscire a trovare una sede definita per installare la statua e la reliquia.

Il ruolo di Pasquale Marrese diventa sempre piu’ fondamentale se pensiamo a quello che ci ha riferito la sua pro-pronipote, quindi la responsabilità che ebbe nella cucitura del tessuto della statua del santo a New York. Ha senso pensare che fosse proprio un crachese con delle abilità sartoriali ad essere stato incluso nella creazione degli indumenti della statua di San Vincenzo di New York nel 1900. Pasquale creò la tela, ingioiellata e ricca di intricati particolari, volendo esprimere tutta la sua devozione: nella fabbricazione si basò probabilmente su quelli che erano i suoi ricordi dell’immagine delle vesti della statua a Craco e forse anche sull’incisione in legno della statua stessa. Con grande probabilità sfruttò un manichino

May 27, 2017

in category: Crachesi in America

Tagged Societá San Vincenzo Martire di Craco

Comments Off on San Vincenzo’s Tailor